Coal Miners of African Caribbean heritage

archive oral history collection

A selection of oral histories from former coal miners of African Caribbean heritage, participants of the Digging Deep heritage project.

(Images and text subject to copyright. T & C apply. Permissions are required in writing from Nottingham News Centre CIC for publishing and broadcasting use).

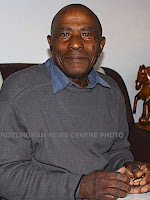

Samuel ‘Vince’ Rubie

Memories of migration to the UK, accidents and diversity in coal mining:

“I was born in 1940, in Brandon Hill, St Andrews, Jamaica. I came to England in 1961 stayed with my aunt who came to England in 1952. My first job, aged 21, was at Manton Colliery, Nottinghamshire and I lived in Worksop, Nottinghamshire.

Read More

My cousin, Briscol Asfold, worked at Firbeck Colliery, Nottinghamshire. I later moved on to Firbeck Colliery then to Gedling Colliery, Nottinghamshire from 1965 to 1973. I remember my check number [miner’s ID token] was 401.

I remember one bloke, a Jamaican man from St Anns, Nottingham who was working in the stable hole and he was packing stones for the roof and the roof came in on him. He was badly hurt and off work for quite a while. We had to spend a lot of time to dig him out. He was lucky not to have any fractures to the head but had a lot of broken bones. He was alright though and came back to work after a couple of years.

Most of the workers at Gedling pit were Jamaicans as well as Polish and other nationalities. For one shift, there were about 300 or 400 men or more working across different seams. There was well over a thousand men at Gedling. With my generation, we were just labourers and the younger men were fitters, electricians and all sorts of skilled workers. I never liked the pit work. It was dusty and dangerous and really hot down in the mine. It wasn’t my plan to stop in mining – it was a job. As soon as I could leave mining, I moved on.”

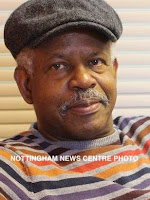

Calvin Wallace

Memories of work life challenges and safety:

“The most difficult thing about working at the pit was the danger. Your helmet was most important for safety and your battery lamp around your waist and on your helmet. Electric lighting was available at certain junctions in the pit.

Read More

The danger, dust, rock falls was bad and the travelling was difficult. The pay, compared to some places, was good. Frederick Darling got hit by a Panzer train. How he is still alive, I don’t know. That’s was why I didn’t want to work on the coal face. Coal face workers, worked through drawings and common sense.”

Frederick Darling

Memories of injury and Illness:

“How can you have good memories when you ended up having what they call ‘miner’s disease’, that’s what the doctors call it, you know, from the hospital consultant and I’ll never get rid of that emphysema. That was what they described it as ‘miner’s disease’ from the hospital.”

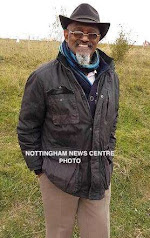

Rupert Menzies

Memories of finding work:

“Well, the dust and the dirt and the noise, you know, couldn’t cope with that, at twenty years old because when I went there, a chap said to me, ‘are you sure you can cope with this job?’ I said ‘yes’ because I were desperate for a job, you know, I wanted to earn some money so I took the job.

Read More

And I wasn’t very good, you know, foreman and bosses were very aggressive towards blacks in them days, you know, we used to get the bad jobs, you know. So, I stopped there [ Gedling Colliery] for about two months working with the props and equipment and then I went on and got a job on the Corporation, as a bus conductor.”

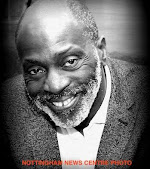

Fitzalbert Taylor

Memories of racial tension :

“There were arguments and fights between men from different countries when people were careless and making mistakes over and over again. I can remember a Jamaican chap called ‘Greeny’ who was being hit by a Polish bloke with a ringer, a piece of iron that releases the coal.

Read More

I couldn’t believe it. The Chargehand was there who should have prevented this but he just looked on. Greeny was not fighting back but he managed to bear it. I jumped over the stage load to stop this. That was one thing you were not supposed to do down in the pit as you could be sacked immediately.

Miners’ Strike of 1972:

The 1972 strike, I was on the picket line. They cooked a big pot of food. People brought food along the Gedling Road to throw into the pot to boil.

‘Come on Big Albert, we want you at the front!’ they said. I thought, when the police see me, a big black man, they will beat me so ‘you go at the front’, I said. I am more sensible than that. You have to be smart when working with them. So I went to the back. It was a case of surviving because you don’t get the same privileges as them. The police drank their soup with the white strikers. I thought this strike is not for us black men. After the 1972 strike, I said I was not going on no picket line again.

The Future

Coal mining would have been a help for young people but this isn’t possible now.”

Kenneth Campbell

Memories of migration:

“In 1961, I had a job in Jamaica, which was a machine operator. After I finish my training as a mechanical engineer back home in Jamaica and I came here because coincidentally as I lost my job and I didn’t have a job in Jamaica, then my father sent me to England.

Read More

I got false information back in the West Indies that you can come to England, you walking in the street of gold and especially if you go into the mining industry you’ll get for five years, you will earn what you need, and you can go back to the West Indies. And so, my time in England was only supposed to be for five years.

Finding work:

I looked around for about three or four weeks and I couldn’t find any job around then that I was really interested in, so I decided to have the mining experience because I heard that it would be a place where you could get your money quickly for five years and then back to Jamaica. But that’s why I went into the mine, so I could work some quick money and go back to Jamaica but it didn’t work out like that. I found work at Wollaton Colliery for nearly four years and of course I leave the industry because Wollaton Colliery closed and I went for a period of time just about three or four months selling. I worked at a place called Staton Iron Works for a couple of years and then my overman, my boss, send back to fetch me back into the mine. My skill, I learned mechanical engineer as a young man back home in the West Indies, that was my trade. And so, working in the mining industry as an underground fitter, you know, maintenance fitter wasn’t difficult, not difficult for me. Eventually I found that was going to be my job. I eventually stayed in the mining industry total about twenty-five years.”

Garrey Mitchell

Memories of camaraderie:

“We used to watch each other’s back and made sure we got on with each other. If miners didn’t get along, the officials would move you. It was a different world down there. But on the surface it was different, things changed. When you had coal dust over you, you couldn’t tell who was black and who was white until you got into the showers.

Read More

Memories of humour:

We used to play ‘hide and seek’ in the coal mine because we finished our work quickly. But one day I nearly died. We were waiting for the loco [train] to come to take us back and I decided to hide in a manhole. I started to feel heavy and sleepy. I couldn’t move my hands and legs and realised it was gas. All I could do was to bow my head forward out of the manhole. Luckily, I felt a gust of air, which brought me back to my senses. It took two days to recover and get better. I never played hide and seek again! I thanked Jesus.”

William ‘Billy’ Lindsey

Memories of racial tension :

“There were arguments and fights between men from different countries when people were careless and making mistakes over and over again. I can remember a Jamaican chap called ‘Greeny’ who was being hit by a Polish bloke with a ringer, a piece of iron that releases the coal.

Read More

I couldn’t believe it. The Chargehand was there who should have prevented this but he just looked on. Greeny was not fighting back but he managed to bear it. I jumped over the stage load to stop this. That was one thing you were not supposed to do down in the pit as you could be sacked immediately.

Miners’ Strike of 1972:

The 1972 strike, I was on the picket line. They cooked a big pot of food. People brought food along the Gedling Road to throw into the pot to boil.

‘Come on Big Albert, we want you at the front!’ they said. I thought, when the police see me, a big black man, they will beat me so ‘you go at the front’, I said. I am more sensible than that. You have to be smart when working with them. So I went to the back. It was a case of surviving because you don’t get the same privileges as them. The police drank their soup with the white strikers. I thought this strike is not for us black men. After the 1972 strike, I said I was not going on no picket line again.

The Future

Coal mining would have been a help for young people but this isn’t possible now.”

Chester Thompson

Memories of migration and getting to the colliery:

“I came to the UK in 1960. I was going to join the army, but when I went I changed my mind. So I went to Bradford and got a job at the Milling Company outside Bradford, in a place called Allerton.

Read More

It was too cold for me so I decided to come back to Nottingham. There’s quite a few people in Nottingham who work in the mines at the time, yeah. So I applied but I didn’t get in first time and then reapplied about two months later and got the job. But they started you off when you go down the mines, they started off as a ganger or a belt job, a conveyor with the coal, then you got to be trained to be on the face. I had training for the coalface and then I went onto ripping.

Well, I caught the bus about 5 o’clock in the morning and I got to Gedling Colliery for about six. By the time I change my clothes, I would be down pit for half six and I would be travelling for about an hour underground on the train. Some of the faces, you got to come off the train then you’ve got to walk it to go to the pit face, a couple of miles away.”

David Henry

Fondest memory of coal mining:

“I aint got no fondest memory at all because I didn’t get what I wanted, I didn’t get what I wanted. The only thing I can say, the people I met down there, I did learn a lot from about life, survival, basically.

Read More

It doesn’t matter what you do, it’s who you do it with. The one brotherhood, just men alone, you know what I mean, you work underground, you come up and shower together in the same shower, all men in the shower, all men running around naked in the shower, all the jokes, you get changed you go out and you come back and do the same thing over and over. It’s the working class surviving, you see, I never thought of it that way until I went down the pit. I suppose if I’d have gone the other way I would have advanced, I wouldn’t have seen that side of life.

Memories of miners’ social life:

I used to go to the Gedling’s Miners’ Welfare. It was ok. It’s a friendly atmosphere to go and meet other folks and just talk and mix with your friends and go for, at first you can go out for a drink with them, find out what they’re like, what we call it, your above ground, up top, you go and have a drink with them and see what they’re like. So, it was like meeting somebody underground and they’re all friendly but when you actually see them in their own space, you want to know are they still this friendly or are they really racist. Like you’ll get many funny racist jokes with their friends, you know what I mean. I used to get a lot of that, they’d take the piss out of a black fella, oh ‘Dave’s alright, he’s one of us’. I don’t understand that.”

David Henson

Memories of finding work:

“I started at Gedling Colliery in 1974. I was first in Newcastle, working in a foundry. There was an advert in the local paper for jobs in Nottingham and I applied for it. I was told their was a lot of black people in Nottingham and that they would imply me there and I would be alright.

Read More

I was straight down the pit in 1974. I had training at Moorgreen for six weeks, then you start from the beginning as supplier in your first year, then I became a belt fitter. I stayed at Gedling Colliery until it closed in 1991.”

Lincoln Cole

Memories of camaraderie:

“It was scary and rough! But if your finger hurt, there was somebody there to give you a helping hand. It was a sad day when the pit closed as so many men were out of work. Mining should still be going on.”

Read More

Thoughts of the Windrush scandal (summer 2018) in relation to the black miners:

“What’s taking place at this present moment, I can’t believe it. It think it’s disgusting. It is disgusting. I have been here for fifty-nine years and at this present moment. it’s like saying, ‘well we get use of everything you have done and now we don’t want you anymore’ and that’s it. It’s not right.”

See: https://www.channel4.com/news/windrush-miners-hold-reunion

Vernon ‘King’ Gregory

Memories of working as a coal miner:

“I found my job at Gedling Colliery through word of mouth as I knew people who worked there. I was living in Lenton, Nottingham and used to drive to work at Gedling but when I first started I used to take the bus. I worked about eight hours a day, shift work

Read More

I was a coal face worker and used a pick and shovel. The shot fire put dynamite into the rock to blow it down. My first wages was £7 and 10 shillings. And each year we had a pay rise.

You had a clean locker in the morning and then you go down to your dirty locker and put your pit clothes on. You show your number to the onsetter and he puts the check number on the board. This made them know you were down the pit and if anything happen to you down the pit they would know something is wrong because you didn’t come out. When I first started at Gedling, my number there was number 2. At Babbington Colliery, my number there was 465. Everybody who goes down the pit has a number to identify you.

Memories of camaraderie:

Everybody helped each other out – it didn’t matter about colour. We got on well together. Quite a few black miners worked on my shift. We got on well together. There were two chaps from St Kitts and were working there a long time before I started. They have both died. One died from coal dust on his chest.”

Wilfred ‘Freddy’ Campbell

Memories of humour:

“I had both white and black friends. We got on alright. It was a very dangerous place and had to work together. We got on alright. The black miners used to go to the ACNA Centre [St Ann’s Nottingham] to socialise. We had some good times.

Read More

We used to run jokes with my colliery mates. Most miners are dead and gone now – like Charlie Davies. There are not many of use left now.

Memories of the strike:

The 1974 strike…we go through it. It didn’t last long, unlike the last one in 1984/85. The 1984/85 strike Scargill was speaking the truth but went about it the wrong way. He should have put the vote to the members. We would have not lost that strike if he had out it to the unions. Scargill went about it alone. I got no certificate or thank you letter when I left the pit in 1986. I never worked again after I left mining. I never kept anything [documents/ objects] from my time as a miner. I finished and that was it.”

Johnson-John Baptiste

Memories of working underground:

“Well, when I came to Nottingham in 1966 to Gedling Colliery from Ollerton Colliery, I did a job bringing materials to the coal face. And then they would train you. When they train you, then you had what they call real hard work. Shovel. Pick and shovel.

Read More

So, you had to shovel, pick the coal yourself and shovel before machines came in. It was all by hand. Hand filling, they used to call it, you know? It was so hot. I had training. Then, when you get out of the training, you was, it was, at the time, before machine came, was hand filling. So, believe in me, it was difficult. . And then I start looking, then we call it ripping, was pulling the roof to make the road. And then, when you move on, come behind you and clear it up and put bars so it’s going, and that’s the road. I worked at Gedling Colliery quite a long time, till the pit close. And the rest is history, in a sense, because that was the only pit in the village, the only mine actually in Nottingham when I came, and they’re doing so well then. It closed, but the history of all the men who died, they build a big memorial, and that is written down.”

Dave Edwards

Memories and reflections of the end of mining in the UK:

“I worked at the last mine in Nottinghamshire, Thoresby Colliery. We were the last mine to close in Nottinghamshire. Kellingley Colliery was the last mine in Yorkshire, the last deep coal mine in the country to shut.

Read More

So, yes, Thoresby was the last Nottinghamshire coal mine. You’d get government ministers come in and promising this and we’re looking into this to see what we can do for you, oh yes, I remember lots of talk.

Well, you had to have meeting upon meeting and over the last three or four years, you had meetings and the targets got stronger and they wanted more coal. We kept trying to make things work. But, it was never going to happen so we all knew it were coming and then eventually you had a meeting, a canteen meeting, saying ‘sorry boys but we’ve tried, we’ve tried but it’s not sustainable, we can’t get any money from the government, we’ve tried to go to Europe for loans and this, that and the other and it weren’t working’ so they just said no, ‘the pit’s going to have to shut’. So, we had a gradual phase-out and development finished one year and then we kept coaling until we called it the last face team then that finished and we went in the shaft team. My team closed the pit basically, we capped it, put the seal across both shafts. At that time, I was the chargeman [supervisor], so we were the last ones out, we were the last ones to finish.”

Reverend Kenneth Bailey

Memories of migration and pay:

“I had a job in Jamaica aged 22 in 1961, which was a machine operator. After I finish my training as a mechanical engineer back home in Jamaica and I came here because coincidentally, I lost my job and I didn’t have a job in Jamaica, then my father sent me to England.

Read More

I got a false information back in the West Indies that you could come to England, ‘walking in the street paved with gold’ and especially if you go into the mining industry for five years, you will earn what you need, and you can go back to the West Indies. And so, my time in England was only supposed to be for five years. But I’m here now what 57 years.

I had some problems when I first started at Wollaton Colliery in 196. I was the first one and then another black chap and then we didn’t get the same amount of money that the white folks were getting. They were talking about money, then we all just started talking. About £6 10 shillings per week, that’s what my wages was. And of course, the white man, the white maintenance workers were getting more than I, they were getting about £7 for the same job. My overman was very, very kind, kind-hearted and he realised I was doing the same work and he decide to up my payment to £7. Lot of the chaps that we worked with they were very upset because the black man was getting the same price.

Eventually, it worked out because those days the union wasn’t as forceful as it is today you see, I’m going back many years now. We didn’t fight as individuals because eventually things ironed itself out so we all just like become like brothers, working in the mine. Once we get into the mine, we are miners, colour had nothing to do with it because we relied on each other for our survival. Once you got into the mine we’re brothers, when we get back out of the mine we’re different. The people there were nice but the thing about it is that, as a black man in the arena, with the whites, you were not on the same pay as them. They were getting more money than you was.”

Alfred McLean

Memories of finding work:

“1978, September, I joined the coal board. I actually left school in 1976 and I went straight into work, I didn’t want to go to college, I didn’t want to continue education. So, my quest was to earn money and that would propel me to buy my first car which I did; I did achieve all of that.

Read More

So, I started working in a textile factory in ’78 and then, sorry, no I left school in ’76 and I started working in ’76 so straight away I went into work. I actually left that job in ’78 so that was the confusion and I joined the coal board at that stage straight after.I had no notion of going down the pit. It wasn’t something I tested out and thought this is for me. I think the only thing, I suppose I was probably a bit mercenary, I just saw it as earning more money, that was my motivation really and the place to do it was well, the pits paid good money at that time, that’s what everybody said, you know, I just followed it. Also, my uncle worked down in a pit, he worked at Thoresby Colliery.His name was James Thomas. So, he worked there, he’s passed away now but he worked down at Thoresby. I couldn’t get a job at Thoresby but he took me along to Blidworth [Colliery] and said they were recruiting because it was North Notts. So, he said they were recruiting so he got me in and at that time, industries of that type, it would always help if somebody inside the place would help you in and pretty much that’s how it works, you know.

Memories of training:

I did my training at Bevercotes [Colliery] which is another colliery further north, going towards Doncaster. So, that was, funnily enough, the deepest coal mine in Nottinghamshire at about 1000 metres down. So, I did my training there, I wouldn’t say training as such, you did most of your training on the job to be honest and there’s something to be said about that because they generally put you with a more experienced miner. I was put with a guy called Joe Baggley, real old-timer, must have been 100 years old when I met him, and he just basically showed you the ropes. Training wasn’t something like theoretic, it was this is how you do it and you were lucky if you were shown twice before you should pick it up.”

Neville Goddard

Memories of being a young miner:

“I remember, it was November 1978 until 1988 I was a coal miner at Mansfield Colliery and Bilsthorpe Colliery. I was aged 16 and a miner for the first ten years of his working life. People thought I was mad – a black kid from Mansfield going down the mine. What made me go down was the cash in my pocket and that I was not really qualified for anything else at that time. Youth and energy was also on my side then!

William ‘Billy’ Rose

Thoughts on finding work in Britain, in the early 1960s

“The jobs we took when we first came here, is job that the natives didn’t want and we took it. As a matter of fact, maybe I know more about queens and things, about England than the people that were born here, because we were taught that way. If you came here [from Jamaica] before 1962, you were British so therefore, there should be no change.”

See:https://www.channel4.com/news/windrush-miners-hold-reunion

Lloyd Brown

Memories of coming to the UK and finding work:

“I came to the UK in 1957 aged 20. We leave Jamaica on the 17th September and we get here early October 1957. I worked at Bentley Colliery Doncaster, Yorkshire. Well, I found it quite enjoyable at Bentley because we were young and there were young men there and more less I came into Bentley and met up with a few fellas from home that were working in the mine.

Read More

I’d say about four or five men came from Nottingham because they wouldn’t employ them in Nottingham.”

Reflections on surviving the Bentley Colliery paddy train disaster, 21st November 1978:

“Yes, well I was one of them that was on it and I believe it was either three or four men died out of my compartment. How it happened we don’t know to this day. We know they said we’re ready to go and the train start moving but whether the driver did not switch the engine off we do not know and maybe when he tried to switch it and it wouldn’t shut and that is where we have the crash. We went for maybe about five, six chain and then the speed. It couldn’t take the curve and it came off and my friend that I was working with, that night he was dead. The funny thing about it, that young man was saying to me, ‘Lloyd I’m going to sleep all day’. I remember somebody shout that we’re going to have a runaway. I remember saying to my mates, them to get down, you know, like sit down in your chair and throw your coat, coat up, you see that is what I’ve did, I do not know if my mate had followed me, I do not know if anybody were trying to get out or what. But that was it that happened to us. I was the middle, second carriage that I was in, the front one was filled up. There was another train that came. They were able men that were there to help others, as I think we were shocked with what happened to our colleagues, that was it. So, it could have been a double disaster if the other train had come out, it could have run into one another.

Jimmi Poyser

Migration stories and thoughts about mining legacy:

“I came when it was, I think it was either August or July 1962 when I came, and I couldn’t believe how cold it was. I had goose pimples as big as marbles. I remember my mum, she tells me that, right, it’s so cold here that if I don’t keep warm, it will kill me, I will die.

Read More

So, the first thing she did, I think probably a week later after I arrived, probably a couple of days, actually. She went to Fords shop in Nottingham, which used to be in Slab Square, I think. Fords, like, they sell all sorts of stuff, clothing and all sorts. And she bought me two pairs of long johns and three vest, were like T-shirts. Thick blue ones, never forgot them. And these long johns were like the cowboys wear in the western movies, the crotch hanging down. They were horrible. So, I used to wear them. Even through that summer, I had to wear them.”

“Coal mining has given me so much experience, not only in human behaviour. We need to be remembered. There’s no depiction. There’s nothing about, because we say, all miners are black. We are, till we get showered down there, when we come out of the pit, and then you can see, oh shit, yeah. I couldn’t believe I’ve done 18 years down there at Sutton Colliery. I remember driving down the pit lane on the Friday, looking at all those terraced houses where the ex-miners live, and think, Jesus Christ, 18 years I’ve walked up here and I’ve driven up and down this road.”

Andrew Nembhard

Memories of cameradie, father a miner and diversity in the coal mine:

“It was intense, it was interesting, it was exciting, frustrating, you can name quite a few feelings really. Overall, I enjoyed it and I am sure a lot of miners will say it’s a good camaraderie at the end of it.

Read More

You can’t explain to a person outside of mining about mining, unless you’ve worked down the pit, so it doesn’t matter where you come from, I suppose, in the world, all miners can actually relate to each other, so that’s a good thing.

It was me dad who introduced me to the pit ‘cos he was well-known then and he got me a job then. I never encountered racism at first because I think my dad paved the way for me. He was a well-known guy down the pit. His name was Herbert Nembhard and they used to call me ‘young Herbie’ when I came down the pit after that. ‘Oh, it’s young Herbie, look, young Herbie’ and the miners then used to talk about him with great passion. ‘Your dad is an amazing guy, hard worker and always chipped in’ and it’s a great thing to hear and you know, you trying to walk in your dad’s shoes.

The good thing about Gedling pit was it was a multinational pit. I think that mentality, the village mentality, kind of overlapped occasionally but you dealt with it. It wasn’t a place for people who were wilting, you know, frail-minded type. You had to be a strong character to survive down there. If you didn’t, people would pick up on it straight away and have you for lunch, really. It helped a lot of black miners working down there and Asian miners, I think that kinda softened it a bit because people were used to that. I think if you’re looking at racism, I suppose, the real point of racism really came when I left Gedling to go to Rufford, being a predominantly white pit, Mansfield.”

George Streete by Mrs Esther Streete & family

Memories of living in a mining community, by Mrs Esther Streete:

“George Street was as a coal face worker and safety officer and first aider. He worked at Sutton Manor Colliery, St Helens, Lancashire from 1956-1985. In 1925 aged 25, he came from Jamaica in 1950.

Read More

He went to the university of Chicago after World War Two. In 1953, we married and moved to Widnes in Cheshire, into one of the miners’ house and had our children. He was very much liked. There were other black miners in the area and at the colliery. At his funeral in 2001, I was pleased about the support of his friends and colleagues who came to his farewell.”

Abraham Aubrey James by Julie & Millie James (daughters)

Memories of mining:

” My father worked at Clifton Colliery and Gedling Colliery and kept a diary with details of his mining experiences, which we treasure.”

Esmond ‘Ezzie’ Liburd by Liam Liburd (son)

Memories of the 1984/85 strike:

“He used to drive, yeah, he used to, sometimes he would, he would do car share, you know, like if they were going the same place. And I remember him saying that when he got to the pits up in Yorkshire, he used to think,

Read More

because obviously the hatred of lots of miners, he said everyday he was just praying that they wouldn’t paint stripper his car or something like that because apparently it was very common. In fact, in some cases, he said the animosity over the strike when he went to Yorkshire was far like, they were more concerned that he was a Nott’s miner than he was black, that was far more of an issue so. He did strike, yeah, he did strike, in the end he did strike, he said, he told me in the winter of 1984 that it was just too much, and he went back.”

Trevor Clarke

Memories of becoming a miner:

“I was doing a job, paint-spraying etc., after I finished my government course on the RAF and I was spraying cars all day and the money was rubbish and all the fellas, they were getting full pay. So, I went into the square one day, Nottingham Market Square,

Read More

and the miners were doing a recruitment thing and I decided to go and check it out. I went and they interviewed me and I quite liked it and the wages they were promising were fantastic and I decided to go for it and I did. I wanted to do something that I liked really and I wanted to work on a coalface and that’s where the money was, working on the coalface. Wages were fantastic and I was coming out with about two-and-a-half times what I was getting paint-spraying so you can imagine that.

What were the conditions like underground?

” The conditions weren’t bad at all. Most of the faces, the newer faces, they had height and working on the bank was okay. One or two coalfaces, you were crawling through to everything. Those weren’t very pleasant but the coal was there to be cut and it was a job to do so we just got on with it. But, it got better as time went on, all the coalfaces got better so we can’t complain about that.

What was it like working with other miners?

” I thought it was brilliant. I made a lot of new friends, things like that and just knowing that you’ve got a wage coming out every week and something to look forward to as well and as you’re raising a family up and everything, you need that money to back you up with everything.

Can you tell us about your background, your heritage, which country?

“I was born in Barbados, a lovely place, I came when I was six-and-a-half, seven years old. Me and my brother, he was a year older than I was and we went to Coventry but we didn’t stay there long, we went to London. I went into a family home, foster home, Jamaican family. Went to school there for a couple of years then when I left, I went into the RAF.”

So looking back at your time as a miner, what would you say was your happiest memory?

“My happiest memory was getting qualified to work on a coalface because it meant more money and everything than I asked for, normal working and meeting the friends I got on with etc. and having a good life from it.”

Oswald ‘Ozzie’ Roberts

Memories of migrating to the UK:

I came to the UK in 1957. I had no family here but friends who assisted me. I lived on St Anne’s Well Road, Nottingham. I first started at Gedling Colliery in 1960 and trained at the Hucknall Training Centre for two weeks.

Read More

After that, you go back to the pit where you’re going to work. We had a chap go to another pit, you know, but I went to Gedling Colliery. They showed you even how to shovel and how even, because we, in those days, we had pony down the pit. We had two stables down at Gedling pit, you know. And they show you how to harness a pony and how to get the coal. Sometimes I did what you call a double shift, if I was on a Friday day shift I could stop till Saturday morning go home Saturday morning, to go back at six, is what you call a double shift.”

Memories of pit clothing:

“When we were there, you used to have to buy your own clothes but after a while, they give overall and thing, and even get it washed you see. They would, well they would give you like a number, you got dirty and clean part, that’s how it works in the mine, you know. When you go to work you have to strip off and go in the dirty part, you know, and you come out and you shower then you go in the clean part. It was two deck, bottom deck and top deck showers and each part got clean and dirty part.”

Did you like that job?

“Yeah, I liked the mines. They were good job. And then after the money goes up, if you on top rate it’d be a hundred per cent. And when I were working, my time was on quarter to six till quarter past two, I used to make overtime and weekend.”

Clyde Forde

Memories of family heritage in mining and conditions underground:

“I was born in Cardiff, in 1960. My dad was from Barbados and he came across to the UK on a cargo ship that was bringing corned beef to Britain from Argentina. The ship docked in Liverpool in 1956 and from there, he had to go to Gorseinon in Swansea.

Read More

For some reason, he didn’t like it there so he left by passed through Cardiff. He met my mother who was from Mountain Ash, [a town in the Cynon Valley Rhondda] in Wales. They had six children. My mum’s mother was Anglo-Indian. I think my dad originated from East Africa.

Coal mining wasn’t something I set out to do. It was more about circumstances than looking to work underground. I was told I had to get a job. So I walked across to the Deep Duffryn Colliery and there was a guy that used to work with my grandfather. He called me and my older brother that also worked there by our grandfather’s nick name. He asked us what we wanted and I said ‘a job’. He told me to come back in three weeks and that he was taking on the first six and that he hadn’t told anybody else. So I was the second person there after three weeks and that’s how I got the job. I worked as a miner from 1977 until 1987.

Were you the first in your family to become a miner?

No. My two uncles on my mother’s side and my older brother went down [the mines]. My grandfather as well. So on my mother’s side it was like a family of miners. Quite a few of them worked in the pit. I had cousins working there, my mum’s brother in laws as well. I was 16 when I started working in the mine.

So what were the condition like underground?

Well…it’s a hole in the ground in it! ( laughter). In some places, it was like working underneath a table and in other places you needed a ladder. If you were at the [coal] face that had a plough, you were on your hands and knees. The hardest part, in the beginning was that they would not let me do nothing. It was more look and learn, rather than get straight in. Once you know what to dos, they would let you have a go because it was all about safety.”

Ivan Seaton Brown

Memories of coming to the UK:

“I was born in Hanover, Jamaica. When I came to the UK in 1954 I think I was 21 or just approaching. I had a brother here in Birmingham.I came on a ship.

Do you remember the name of the ship?

Yes, Castel Verde.

Read More

And how long was the journey?

Twenty-one days, I think it was.”

Memories of finding work:

“I started at Bentley Colliery in 1957. I went and asked for a job. I could remember it quite clearly, the personnel said to me when I went, he said I could give you a job but I haven’t got a proper form to fill in, they’re all at head office. He asked for some to be sent to him and they hadn’t arrived yet. Anyway, I went to about three or four more pits and the same thing happened. So, I found myself at the Head Office and told him that the personnel officer sent me, which was untrue. Anyway, I got a form and I went straight back to the place and when I went back, they were just closing down to go home. He said, ‘I’ve got no time now to sort things out for you so, will you come back in the morning’. I was there before the offices were open the next morning [laughs].”

Memories of first jobs underground:

“My first job was what you call hand filling the coal and packing and drawing off, you wouldn’t know what terms that is, the steel you set, like when you finish working you advance, what we call a conveyor.”

Memories of camaraderie:

“Well, I’ve always admired how helpful the rest of miners were, how supportive, I should say. You know, if you’ve got a problem, they’ll all stick together. That were one good thing about mining, whether you’re black or white sort of thing, you’re supported, you know. If you have a case to fight they help you to fight it.”

Sheadrock Allen

Memories of migration and finding work:

“I was born in 1929 in Jamaica. I came to England when I was 19 in 1948. I found a job in Brodsworth Colliery, South Yorkshire. I was there for 15 years. I was a ripper. Doing ripping you know. I worked on the pit top and then I got on the pit and then I trained for working on the face.

Read More

I do ripping on the face, back ripping, front ripping and everything, you know.”

Memories of team work:

“I worked with some miners who were really good, you know, and I worked with them and enjoyed to work with them, some of them, you know. I had some odd racial word and everything you know, and you just take it and make the best”.

Thoughts on the legacy of miners:

“It’s that the miners have done a lot for this country and people should realise that the miners were the backbone of this country and we should be treated better in some ways but more than just look and say they’re just a miner. We done a lot for this country as miners, especially the black people that go down the mine and work down the mine because we have to work in the mine and work in the mine against all odds. It was a dangerous place to work and likewise, you have some of the people who think oh, just because he is a miner, he’s just a miner. It’s alright to say he is just a miner but send them to do the work that the miners do – they couldn’t do it.They couldn’t do it because it’s something that you have to have guts and likewise, save your friend’s life as well as saving your own life. So, there is a lot of that experience, you know. You don’t say well, you’re looking after only yourself, you are looking after your friends because every man should be friends, I don’t matter about the stones thrown at me because I give them it back, I give them it back, you know.”

Memories work satisfaction:

“I enjoyed working down the pit, even when it’s hard work but I like to work hard. I mean, I like to work hard because it helped me along very well and showed me the way. Likewise, mining showed me how to live with people, that’s my experience. It doesn’t matter how hard it is, you work around it and live with them and that’s the way it go.”

Abiodun ‘Mac’ Williams

Memories of skills development:

“My first role was a labourer or as they called it in those days. Then I went for underground training at Horton Colliery for sixteen weeks, came back, worked down the mine for a few weeks and was offered an office boy in the Colliery offices, office boy/compose boy.

Read More

After that, I did further underground training, went underground for a few weeks and was offered a post in the Ventilation Department at the Colliery in 1961. In 1961, I worked as an Assistant Ventilation Officer and I was encouraged to take further education and then I went to Durham Technical College, got qualified to be a Colliery Ventilation Officer. In 1968, I was appointed the Collier Ventilation for the colliery. In the meantime, I was studying Business Studies at Sunderland Polytechnic and Durham College for Mining. In 1971, I left the Coal Board simply because there were lots of small pits closing, Durham was one of the biggest collieries on the coast; Gordon, Easington, Weymouth, and the colliery managers were being given the specialist jobs, which I wanted. I wanted to be a safety engineer or a ventilation engineer, so I left.”

Dennis Gibson

Memories and thoughts on mining legacy and young people:

“Yes, it was a good job. It was hard work. I think it set me up because I know hard work, so anything I do outside of the mine now is easy to me because I know hard work and I’m still doing a bit of hard work now.

Read More

You have to work for what you want in this world, don’t you? Education, whatever, you have to cut it until you find it and just get on with the best of it.

I: What would you say to young people who don’t know a lot about mining history?

It’s gone now so some of them are not going to see that. They’re not going to be able to go down the mine. It was hard at the time, it was hard for black men and they always used to put you on the hardest jobs. The ripping, I can see where my father and some of his friends and colleagues have gone through some pressure just to feed my generation and my generations coming behind me. They have to look for what they’ve got in this country. Depends how much brains they’ve got, always study. Even if you’re like me on this job where I’ve left the mines, studied and gone to college to be a bricklayer. Maybe I got into it late but it’s still racism, they always watch you. You have to try and do the best you can because even if you’re dumb up top, you’re still going to be low, so why sit down and get nothing anyway? Education, I always say and I’m not that well-educated but even with my brains, I’ve done alright for myself. So, I’d say work hard, do the best you can.”

Royston Thomas

Memories of pay and community:

“In them days, they say it was the best paid job, labouring like, it was the best paid labouring job but it wasn’t. As I say, you have to work hard to earn bonuses to make up your wages.

Read More

Some people like being a miner because some of them work like a community, you know, they have their mates, their friends that they see every day, you know and things like that. Like a family underground.”

Lloyd Williams

Memories of going training and going to the colliery:

“I was born in West Portland, Jamaica in 1955 and was 13 when I came to the UK. I came to the UK as my dad was already here and he sent for me, as he was living in Nottingham, in May 1968. I went to Elliot Durham School.

Read More

I became a miner in 1979, aged 24.I found out about coal mining through my wife’s dad worked at the mine at Moorgreen Colliery. So I thought I would try that. I went for one day at Moorgreen but then started my training at Gedling Colliery. I think I got six months training. the training was useful as you learnt what to do. You learnt to do the rails, the loco, the slippers and stuff like that. My first were that it wasn’t what I was expecting. We clocked in for 6 o’clock but you have to get the man rider underground. My shift was about 7 and a half hours long. I used to catch the pit bus to work from Bulwell. I used to get up at 4.15am and I used to walk it done to Main Street and the bus used to pick us up there. There would be about fifteen of us on the bus. I think I was the only one [black man] on the bus.”

Hopeton ‘Harry’ Lindsey

Memories of duties and machinery:

“Well, I guess when I started, I started ganging. The ganging is like bringing material to the face, you know, like what they’re gonna need on the face. The face is where the coal come off, if you know what I mean?

Read More

We have two gates – we have main gate and tail gate. The main gate is where the fresh air go through, the tail gate is where the stale air comes through. A face bank is at Gedling, it used to be about 350 metres. A face is, where the cutting machine take the coals off. Yes, I started, as I say, ganging, then I gets training to the face for about, was it about two months’ training on the face? All sorts, it was more or less, it wasn’t, it was common sense. It wasn’t anything technical or whatever it is, you just might have to use your common sense and see where danger is and make sure you are safe. That’s what it’s all about, protecting yourself because at any time on the face, it could cave in if you don’t make sure you are safe the best you can, ‘cos you’re cutting the coal and we have some hydraulic props or I don’t remember what they’re called exactly, hydraulic props, yes, on the face. You know, as I say, they was about 350 metres long and we have these props going along, they are hydraulic ones, pumped up. Sometimes the roof and top just breaking up and collapsing and so forth.”

Victor Wright by Anthony Wright (son)

Memories of Victor Wright, by Anthony Wright (son):

“My dad was born in 1926, in Trelawney Jamaica and came to the UK in 1955. He used to work the night shift and come home, light the fire and cook breakfast for the six off us.

Read More

Then he got a few hours kip [sleep]. One day, he was coming home on a bus, he dropped his wage packet and had a stroke. He lived for thirty years after the stroke and passed away in 2010 aged 84. He never went back to Jamaica once. He meet my mum in Cardiff, Wales. My dad worked at Nantgarw, mid Glamorgan, Wales, which closed in 1986 and Big Windsor Colliery. He worked as miner for around 25 years from 1955 until 1980.”

Oswald Thompson

I: Where were you born?

OT: Jamaica.

I What year did you come to the UK?

OT: 1959.

I: How did you find work as a coal miner?

OT: I wasn’t a coal miner, a surface worker.

Read More

I: So how many hours a day did you work?

OT: Maybe eight, maybe eight.

I: And where were you living at the time when you at Gedling Colliery, yes where did you live?

OT: Just to, in Radford.

I: How did you get to work?

OT: The bus.

I: Ok, was it a Skills bus or something else?

OT: Skills bus.

I: Ok. And can you remember any other miners, any Afro Caribbean miners when you were there?

OT: It was fun.

I: It was fun?

OT: Yeah.

I: How many do you think were there at that time, when you were there?

OT: Maybe 500, yeah 500.

Robert ‘Bob’ Johnson

“Happiest memory what me have, me time going to me work, worked there [Gedling Colliery] for 24 years and I am, am still alive and I didn’t get no accident, that’s me you know. Some people who go to work and get themselves in an accident for get the money, when you’re dead…

Read More

or you’re cripple money now no use to your body when you’re feeling pain. So when people, whenever time that you do it, go to work you should always make sure you look for safety for yourself.”

Ernest Cuffe

Memories of worklife:

” I was born in 1924 in St Elizabeth, Jamaica. I came to England aged 32 in 1956. I had family in Nottingham, my bother. He had been a policeman in Jamaica before. My first job was on the railway in Colwick, Netherfield (Nottingham) for about two and a half years.

Read More

When the engine go out in the morning and came back in the evening, you gots to wash out the boiler and get the engine ready to go out in the next morning. Get steam and power before it can go out in the morning. I got to go up and down, go in there and clean it out, you know, come out, after you finish that you wash it out, get the water in back, get it hot, put the coal in the boiler and build the steam up. I let found work at Mansfield Colliery [Nottinghamshire] and Shirebrook Colliery in Derbyshire. I was living in Lenton Nottingham at that time.

You haves a boy take you around underground and show you what the work is like and what’s going off. After you’d finished twenty-one days, you’d go back to Shirebrook and start work there. When you went back there, you started work on the conveyor belt and everything, carry material to the coalface and all that, you know? I wanted face training … You get more money, you see. So, I came back to Gedling [Colliery] and got the job. I start work on the conveyers, like what I was doing first at Shirebrook, for not even, a couple of months, then I start me [coal] face training. You work with somebody to teach you what’s it like, the two of you work together. You shovel coal, at that time it was all pick and shovel. You gots to go there in the morning, you go down the mine, take the train, take it to the coal face and then you start to work what you was supposed to be doing.”

Keith Burt

Memories of working underground:

“I worked at Yorkshire Main, Edlington and I started off at Bentley Colliery. I was born in 1958. I started there after leaving school. I think I were, 1974/75 I left school. My training? I started, I wasn’t old enough to go down th’ pit when I first started,

Read More

so I was in woodwork shop ‘til I turned eighteen, ‘cos I couldn’t work nights then, you couldn’t work nights ‘til you were eighteen. I started in th’ woodwork shop and I used to go down th’ pit to put brattice cloths up, cloths up the middle and stuff like that. When I were eighteen, I did me training at Armthorpe, which was Markham Main and then from there, I went back to Bentley pit and then I got married and moved to Edlington and I were at Edlington ‘til it closed. I started off in th’ carpentry shop at Bentley pit, making air doors and things like that for down th’ pit and then after I did me training, I was a haulage man for so long. Then I did me face training and then went onto th’ face after that. Main gate rip, barrier rip, chock man, machine man, I did all kind of things on there.

Can you remember your very first day underground?

Keith: Yeah, I can, bloody frightening, it was very frightening. We were going down th’ pit actually on the face itself. Going down th’ pit before, you know, going to other places, it wasn’t too bad but actually going onto a coal face, yeah, it were a different experience. Very different experience – noisy, dusty, weight coming in all th’ time, it was the weight coming on that I had to get used to, it went ‘bump’ and everything shook.

Do you remember any other black miners at Yorkshire Main Colliery?

There was one that we used to call ‘Black Sam’, he were an African gentleman. His last name were Williams and he used to tell us tales when he first come to the’ UK, he worked up in Wales. Well, in Wales, Williams is a very popular name. He got on like a house on fire, you know what I mean? Then he moved from Wales, I think he lived at Balby, just outside Doncaster and he used to work at Yorkshire Main but I don’t … he’s probably dead now, Sammy, it were a long, long time ago. Then, oh let me see, there were a few other but we were all on different shifts so, I knew whereabouts they lived in th’ village but we were never on th’ same shift, we were always on different shifts. Altogether there were about five.”

Lawrence ‘Larry’ Ferron

Memories of working life and witnessing an accident:

” I was born in 1934 in Clarendon, Jamaica. I came to the UK in 1957. Well, it was, I thought it was the mother country, so I come, come, come to get something from the mother. Come to get some work. I were twenty-three. I knew somebody that was here, and they received me in the country.

Read More

And how, did you come here by plane or boat?

LF: On a boat.

I: And do you remember the name of the boat?

LF: SS Montserrat. I work at Gedling colliery. It wasn’t as easy as I thought, but I spent all these years down there because, when I came here, they came to where I was living and they wanted me to sign up for National Service, and I didn’t wanna go in there. I didn’t wanna go in National Service. They used to send people maybe to Cyprus those days, when, you know, and thing like that.They came to my house and they register me. I said, I told them I’m in the mine, and they said, whenever time you leave the mine, if you leave the mine before you reach the age, then you’re gonna go to National Service. So I went down there, and when the age was up, when the time was up, I might as well stop there. And I stop, then I grow a lot of potatoes, yeah.

Well, I train at Gedling in the coal face to take the coal off, you know. And the training face, it used to be four and a half yards of coal, which it is, I think it’s about nine tonnes or something. I can’t remember how much ton in the four and a half, you know. But that’s where we trained. I used to train on there, so. And then, when I finish it, then, you know, I go on other jobs.

So did you witness any accidents when you were a miner?

LF: Well, I remember I was on the face at the time, and the roof and everything came down on him. He was on the machine. He should be driving the machine, but he stop and come back to help the guys. And he were going away from them, and they couldn’t catch up with the work, so he came back to help, you know, and the roof came down on him. I can remember that, yeah. I was on the shift, yes, that time and then they took the body out the, out of the pit, like, you know. I didn’t, I didn’t take it out, like, you know, but, you know, just one of those things. I went to the funeral. They cremated him. Yes, I remember, yeah.

Hervin Althmond Henry

Memories of migration, the canteen and pit rules:

“I was born in 1938, in Clarendon, Jamaica. I came to the UK in November 1961. We come from the West Indies, from Jamaica and we come over here. And during the war, in London men to go to their day job, some gone to the war.

Read More

So we have to come over and help out and all them houses in London, and build them up again and thing like that stuff.

You have to get up some time in the morning. And some time when I wake up in the morning, like at three o’clock, I can’t lay down there. I have to get up. Because, if you do, you fall asleep, you can’t get to work. Yeah. Sometimes they’ve had two buses that used to take men to work at pit. The bus drop men off at the pit. Yeah,Yeah. And then the canteen, full of men and, it were nice. It were nice. I enjoy myself.”

You can’t go down the mine and say somebody call you certain name, and you go fighting. You’re like, no, not down there, fighting or anything, down the mine. Nothing like that. Yeah, you got the rules. Yeah.”

Vernal Roden

Memories of socialising and racism:

“I started at Gedling Colliery in 1959 and was born in Barton, St Catherine, Jamaica in 1935. When it comes weekend time and we as black young men, were going out, we make sure that we go out in, so if there’s six of us, we keep close together.

Read More

And when the Teddy Boys, like the MODs and the Rockers and the Skinhead they come to us, and make sure we stick together because if you didn’t know what to says, take the words and are scared and you run off, that they separate you, like to see a lion who separates those. We used it as protection because even if you don’t know what to say, plenty of we get beat up and you go to the police station. At the time, the police, them have themselves they don’t like you black people and they will says, you know them. I says no and they will says to you, ‘see get to know them and they are dressed and come back to them’. At the time, you get a good hiding, see what I mean? It was like hell. And when we tell our children what we go through, that if you see a room over there to let out or whatever it is, you know, the most people them who do know what to say is more regards and respect is the Indians. But most of the whites, they think we are dogs.”

The best place that we used to go and get enjoyment is the Palais (nightclub). We used to go to the Union pub. And the places you go on and can sit down and have a drink is the Wine Aces in town, the Aces pub in town. I’ve been to the Calypso Club [Nottingham] , that was mostly for the blacks then and all that, you know, yes.”

Astley Willis

Memories of

“I was born in 1942, in Clarendon Jamaica and came to England in 1961. I trained at Moorgreen Colliery for about two weeks. I worked at Gedling Colliery with my friends Freddy Campbell and others.

Read More

What are your thoughts on the miners’ strike of 1984/85?

Well, I didn’t reckon much to it, actually. It didn’t, it didn’t bother me, if you know what I mean. Yeah. They were calling us scrubs [scabs] and all that, snubs, you know, because some was working and some wasn’t working, you know. But I got a family to look after, so, you know, I couldn’t afford to stop working, you know. A mortgage to pay and all that, you know, so I still carry on working. Yeah. Outside the gate, yeah. Well, they stop you from going in, you know, but, like I says, I got a family to look after, so I got, I couldn’t afford to stop working. I was made redundant after the strike and worked for Boots from 1985 to 2005.

Colin Raymond

Memories of his job interview for colliery work:

” I was born in 1959 and worked at Gedling Colliery from 1977 to 1989. It was hard at first. I was a very, very hard job but it was the money that kept me there as a young person. They money was good but I didn’t really like the job.

Read More

My dad, my old man, found me the job. He came to me one day, knocked on my bedroom door and said’ I’ve got a job for you. Get up and get ready’. I said, ‘What do you mean?’. He said, ‘get up and get ready!’ So obviously, you didn’t really back chat your parents, so I went. I turned up at Gedling Colliery. I remember the man’s name called Mr Hopkinson. Me and my dad went in. I remember Mr Hopkinson talking to me, asking for my name. But I was acting a bit cocky because I really didn’t want the job so I was doing everything not to get the job. The next minute, Mr Hopkinson passed me this coin with the number 125 on it. All I remember next is from Mr Hopkinson is, ‘You start on Monday’. I remember saying to myself, what a weird interview this was! It was really weird because I didn’t want the job but got the job. I trained at Moorgreen Colliery first. I worked at Gedling on top [surface] first, in haulage, packing items for the workers down in the bottom [on the coal face].”

Clarence Tucker

Memories from his friend, Councillor Malcolm Jones

“Ah, can I say, a wonderful man. Um, I moved to the village of Tonmawr, south Wales in 1957, and, unusual, you know, cos I’d been covering a large community where we weren’t, ah, we didn’t have any coloured or black, black, isn’t it, members of the community.

Read More

And moving to Tonmawr, this little village, and we had a black family living here, working. And, as I say, but a big part of the community, they were.

His name was Clarence Tuckett and he was a miner. Um, his father, apparently, the story, you know, cos I was an incomer into the village. His father worked on the ships, ah, cargo ships, and used to come into Cardiff docks on a regular basis. he used to tell me stories. His father continued to work on, ah, the ships going out of Cardiff, and he used to, he used to tell me stories about, um, when he saw his father coming home, because he, his father would have been visible about a mile and a half from the house, you know. His house was only about 100 yards from the Garth Colliery in Tonmawr, and obviously after school and growing up, Clarence went into the colliery to work. And in the colliery, it employed about 200 men. And, as I say, became big part of the community. He had a beautiful singing voice. And at weekends, people used to socialise and go drinking, you know. Clarence would always be the star turn.

Horatio McLean, by Sandra McLean (daughter)

Memories of mining:

“Well it started with the arrival of the Windrush and a Jamaican came over on it named Horatio McLean and he came to be in the Nottinghamshire mine field. He was at the Bilsthorpe Mine and at that time in 1949 there were very few going into the mine…

Read More

and he did lodge with a family in Bilsthorpe Village. It was a small colliery village and everybody knew everybody and the amazing thing about it for me as a six year old, seeing this big black man for the first time in my life was how friendly the villagers were towards him. Because at the side of the pit head, they had the big playing field and they used to have cricket matches during the summer and we used to picnic on a blanket in the field and as the miners went on and off their shift. They used to come and stand at the side and cheer him and clap and, you know, they really took us into their community so to speak. And at Christmas the miners, all year through, used to put money aside for a Christmas party for the children so that my brother and I, when Christmas come we went into the colliery canteen and we had this big oh, Christmas party. We also was taken to other houses in the village where other miners and their wives lived and their families I should say, and it was a quite a nice experience.”

Samuel Case

Memories of migration, finding work and camaraderie:

” I was born in 1931 in Clarkson Ville, St Ann, Jamaica. I lived in the UK from 1955 and returned to St Ann, Jamaica in 1982. In 1956, I worked at Bentley Colliery in Yorkshire for one year and moved to Welbeck Colliery in Nottinghamshire from 1957 to 1982.

Read More

I came to Derby, England with my brother, Lindon Case, who also became a miner at Welbeck Colliery. I worked extremely hard in a factory in Derby and the wages was small and I found it very difficult to support my family in Jamaica and myself. So I decided to work in the mines instead as this was the best wage at the time. I went to a mine in Doncaster and wanted to work on the coal face to get a better wage, to be able to send money home to my mother as my father had already died. They said I had to get on a waiting list to work on the face. I felt that this was not good enough so I talked to some of my friends in Derby who told me that Welbeck Colliery in Nottinghamshire needed workers. This was in 1957 and so I moved to Mansfield in Nottinghamshire, which was near to Welbeck Colliery. Everything was good at Welbeck Colliery and it was hard work. I had a serious accident underground in 1978. I didn’t enjoy the work but had a family so had to make ends meet. Other black miners at Welbeck Colliery were David Fraser and Linton Thompson from Clarendon, Jamaica. They were no problems working with the other men. Black or white, I just looked at it as us, as one.”

Kenneth Jackson

Memories of migration, injury and life after mining:

“I was born in Clarendon, Jamaica 1940 and came to England in September 1960. I returned to Jamaica, where I now live. I worked at Gedling Colliery from 1961 to 1986 on the coal face and heading, on the headway, helping to make the roadways underground.

Read More

It was hard work and most of the time awkward as you were on your knees a lot. I had my finger cut off and sewn back on and a back injury which I am suffering from now. After the strike finished in 1985, they were giving voluntary redundancy so I took the redundancy and left.